Table of Contents

The coatings industry has experienced a variety of supply chain issues over the past 50+ years, but none as severe and broad-based as what is now being referred to as “The Great Supply Chain Crisis” of 2021-2023. While it was catalyzed by an event—the onset of the global pandemic in 2020—the seeds of such a crisis were borne in the global supply chain for many years prior to COVID-19. All that the pandemic did was to knock down the first domino in a complex configuration of dominoes that had been lining up for years prior—the rest of them fell as a result of the way in which they had been positioned for at least a decade or more prior to the crisis. Bottom Line: The Great Supply Chain Crisis may appear to have been triggered by the global pandemic, but if the pandemic had not occurred, something else would have eventually caused it to happen. A house of cards is always destined to collapse—the only unknowns are “how long before it falls” and “who or what will cause it to fall.” Fall it will, however. . . .this is not speculation, but rather a fact of nature, physics, and common sense.

As we sit here three years later, the real questions should not be “Will such a supply chain disaster ever occur again in the future,” but rather, “When will the next supply chain crisis hit the global manufacturing network?”

Following The Great Supply Chain Crisis, a lot of action was taken to prevent such an event in the future—action by businesses, both small and large; local and state governments; governments of countries around the globe; cooperative organizations, such as the World Bank; and global non-profit organizations, such as the Red Cross. A lot was learned, and a lot of the learning that was applied to the various areas of business, government, and global cooperative organizations was of a very positive and proactive nature and would certainly help to stabilize the global supply chain in the event of another unexpected event, such as COVID or similar event destined to affect the entire global community and wreak havoc with the complicated arteries of commerce that carry the lifeblood of the global economy in them. What if, however, the next situation that negatively affects the global supply chain is neither sudden nor expected? What if, instead, it is a predictable set of circumstances that we know will cause such a problem, but which we cannot predict with regard to when it will have an impact?

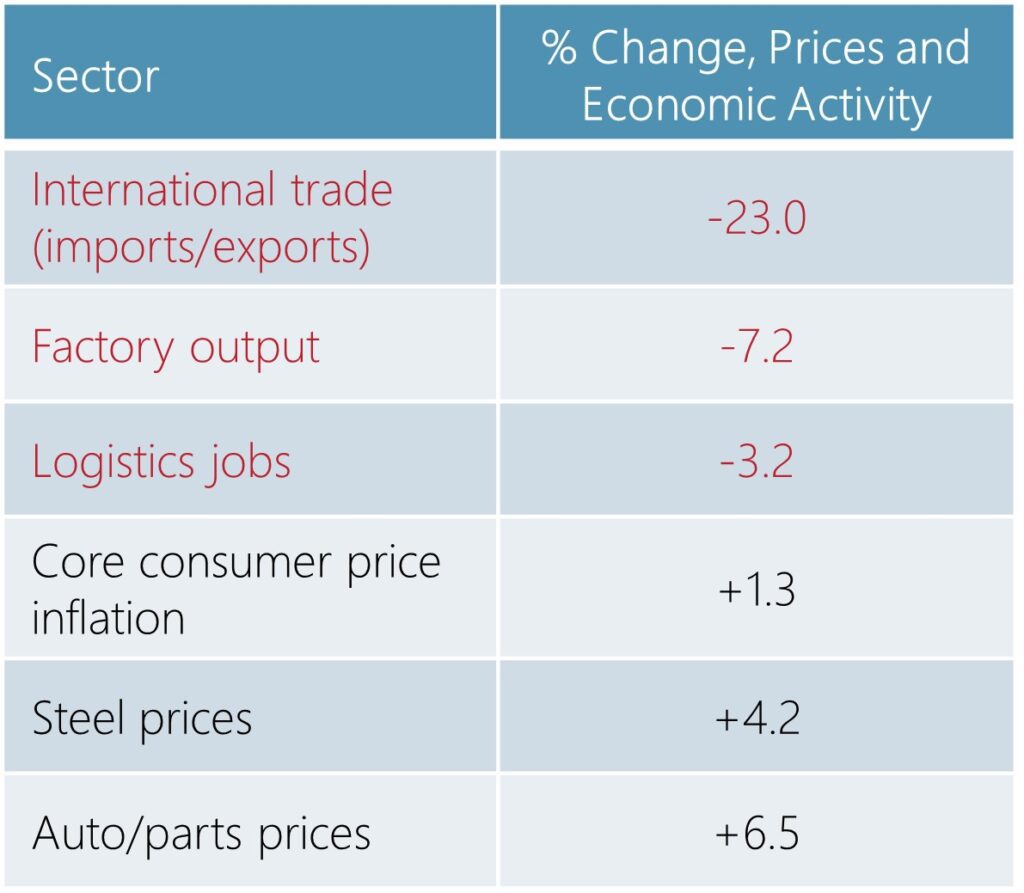

To address that potential scenario, let’s take a look at some of the effects on the global trade corridors that took place during the years 2021-2023. See Table 1.[1]

There is no doubt that trade among the U.S., Canada, and Mexico increased, although exports from China to the U.S. declined, as did exports from China to Hong Kong. Exports from the U.S. to China remained approximately the same, however—with only a 1% drop over the three-year period.

The forces that will shape the future flow of trade are already in play. The real question is not “Will future global trade look different from today,” but rather, “How will future global trade look different from today?”

Geopolitics and Economic Outcomes: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

Whether ongoing tariff issues, the War in Ukraine, or cybersecurity controls, all companies are affected in some way, and to some degree, by those issues that affect global trade and which have already created a variety of negative situations for global industry participants. This is news everywhere. What is not typically discussed in the news, however, is that negative situations very often lead to opportunities for positive change, as long as one is open to change. McKinsey, for example, has identified 10 “key value drivers” that should be evaluated by business leaders for potential opportunities arising from geopolitical issues of one sort or another[3]:

- Trade agreements

- Import and export controls

- Domestic environmental, labor, and immigration policies

- Tariffs and other trade barriers (e.g., steel, aluminum)

- Domestic industrial policies (e.g., subsidies, tax breaks)

- Foreign investment restrictions

- Sanctions, embargoes, and restricted lists

- Multilateral cooperations and alliances

- Conflict (e.g., Ukraine, Red Sea, Taiwan, Ecuador, Gaza, et al.)

- Technology, intellectual property, and cybersecurity controls

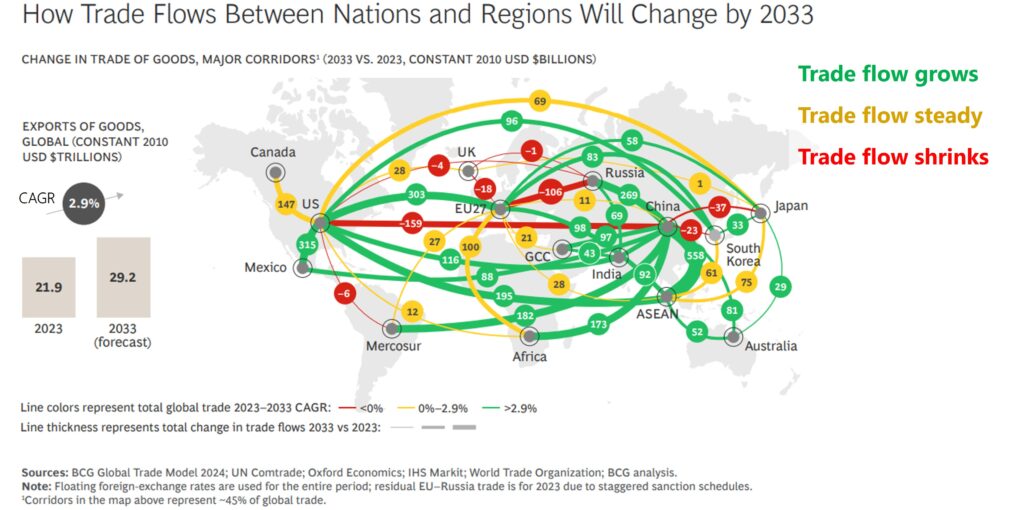

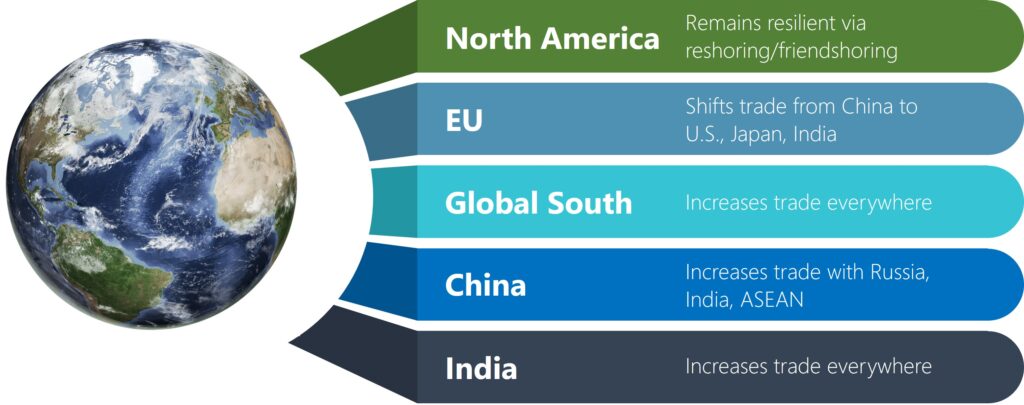

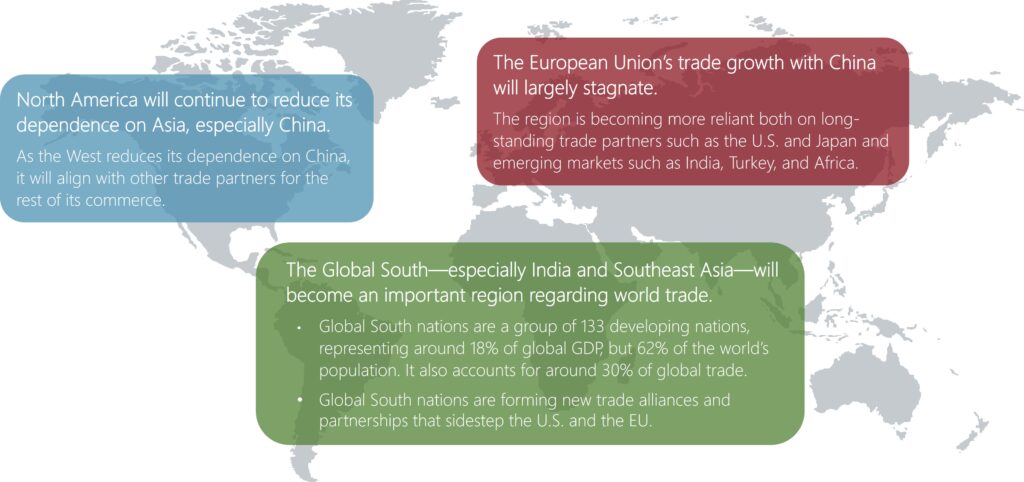

On the largest scale possible—global trade—we are seeing the early stages of what are likely to become major shifts in the years ahead, with regard to “who trades with whom” and how this will affect global regional trading patterns. For example, it is highly likely that there will be decreased trade between both North America and EU with China, but increasing trade between North America and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)—and both the EU and North America will be increasing trade with India and selected other countries in the “Global South,” such as Mexico, Brazil, Thailand, Viet Nam, Nigeria, and Egypt. See Figure 2 and Table 2.[4]

1South = 133 nations of the UN G77, excluding China

2West = U.S., EU27, UK, Canada, South Korea, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand

Looming Challenges for Traditional Approaches to Stable Supply Chains

What became clear following The Great Supply Chain Crisis remains true today: just-in-time (JIT) inventory is dying. It works well for a single, powerful producer at the end of the value chain, but it comes to grief when more than one link in the production chain also demands JIT. Similarly, reshoring (or nearshoring, friendshoring, ally-shoring) for critical products and the reduction of shipping costs is being embraced by many companies worldwide. We are already seeing various steps being taken to reduce dependence on Chinese specialty chemicals.

Geopolitical considerations are increasingly becoming a part of the thought process in industry participants’ plans for the future, whether tactical plans for the near future or strategic plans for the longer-term. It is imperative that we be taking into consideration “what if” scenarios involving, but certainly not limited to:

- Resolution—or indefinite continuance—of the Russo-Ukrainian War

- Suez Canal disruptions

- Potential conflict between the U.S. and Panama over ownership of the Panama Canal

- Tariffs/potential tariffs/threat of tariffs

- Potential invasion of Taiwan by China

- The “Greenland Question”—the U.S. is not alone in coveting its potential military importance and strategic mineral supply

- Changes in the balance of power in the Middle East—fallout from the Israeli/U.S. bombing in Iran

- Syria breaking away from Iran and seeking backing by Saudia Arabia

- Gaza Strip—major differences in viewpoint among Arab nations and U.S.; possible U.S. designs on Gaza Strip

Additional challenges include:

- Materials substitution

- Replacement of materials requiring paints and coatings by non-paint-reliant materials

- Decorative architectural: Fewer paintable surfaces

- Industrial and specialty: Clear and color wrap films, larger windows in vehicles

- Market consolidation

- Consolidation of paint and coatings formulators and raw material providers

- Paints and coatings formulators continuing to consolidate globally, with major players such as Sherwin-Williams, PPG, AkzoNobel, and Nippon driving M&A activity

- Labor shortages

- Labor shortage leading to higher automation and increased use of robotics and. . . .

- Faster turnaround, faster return-to-service coating application technologies

- Fewer immigrants to take jobs that workers already in the country do not wish to perform, leading to lower productivity and forcing the use of greater automation—with consequent discontent among unions

Trade Outlook

China is the 800-pound gorilla in the Global South, but its total trade growth will be limited to an estimated 2.7% annually over the next decade, well below the current average real annual GDP growth estimate of 3.8%. There are a number of reasons for this, both economic and geopolitical.

China’s trade within BRICS+ (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates) is projected to account for 44% of China’s total forecast trade growth over the next decades, and its trade relationship with Russia is projected to increase significantly. Bilateral trade will grow by $269 billion by 2033 (6.3% CAGR).

As China’s trade with the U.S. and EU slows, it is growing strongly with much of the rest of the world. We project that annual two-way trade with the West will contract by $221 billion by 2033—representing an average annual decline of 1.2%. (NB: The cost of imported Chinese goods would increase, however, by more than $200 billion if no alternative sources were available and if import volumes were to remain constant.)

We project that China’s trade with the Global South, by contrast, will surge by $1.25 trillion by 2033, representing a CAGR of 5.9%. This shift will support China’s geopolitical agenda of reducing its economic reliance on the West while deepening ties with major emerging markets.

India is emerging as the other big Global South trade story, as it pursues favorable relations with most of the world’s major economies. Boston Consulting Group predicts growth of 6.4% CAGR in India’s total trade through 2033, to $1.8 trillion; its trade with the U.S. is expected to more than double over the next decade, to $116 billion in 2033.[5]

The effects of geopolitics are escalating—we are even now witnessing seismic shifts in global trade. The U.S. has already violated the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA; former NAFTA) by imposing new tariffs. Depending upon the results of the renegotiation of the trade agreement between the U.S., Mexico, and Canada in 2026, it is likely that annual trade between the U.S. and Mexico will increase by $315 billion by 2033, representing a CAGR of 4%, and U.S.-Canada trade will grow by $147 billion as companies serving North American markets shift more of their supply chains.

Washington is concerned that Chinese firms’ intent to circumvent high U.S. protectionist barriers against low-cost Chinese electric vehicles (EVs) and other goods by assembling them in, and exporting them from, Mexico, thereby taking advantage of its “duty-free” access under the current USMCA. One issue to watch is whether the U.S. will leverage the USMCA renegotiation to seek to have Mexico screen Chinese foreign direct investment in its North American manufacturing value chain. At the moment, this would be anyone’s guess. . . .Currently, this is essentially how China is slipping things into the U.S. via Vietnam. And so it goes. . . .

“Friendshoring” is a new term (along with “ally-shoring” and “nearshoring” and a few other similar terms) redefining North American trade relationships, where trade relations are bolstered with U.S. allies. U.S. trade with the EU, for instance, is projected to grow by $303 billion, a CAGR of 3.1%, by 2033.

Companies must consider the risks and opportunities created by geopolitical shifts that will alter their supply chains and business strategies and develop game plans for adapting to disruption. As trade lanes evolve, consider shifting your supply chains to make them more robust, cost effective, and resilient.

Tariffs: A Genuinely Complex Issue

Multiple studies of the long-term effects of tariffs in the 20th and into the 21st centuries indicate that, with only a few exceptions, tariffs do more harm than good. Though they may provide short-term relief and often give the public a psychological “high,” tariffs typically act as painkillers—and like painkillers, they just give temporary relief.

The Great Depression was fueled, in the view of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and many others, by sky-high tariffs that had placed the U.S. on “the road to ruin” by inviting retaliation and discouraging investment. While there are many differing opinions on the value of tariffs, history clearly shows that, while short-term tariffs may be used to bring about strategic changes in relationships among nations, long-term tariffs are always damaging to the nation that imposes them. In the U.S., for example:

- Tariffs reduce the demand for foreign goods, which has historically led to the strengthening of the dollar, resulting in less global demand for American goods.

- The 2002 tariff increases on selected steel products backfired—U.S. Senator Lamar Alexander (R-Tennessee) observed that since “there were 10 times as many people in steel-using industries as there were in steel-producing industries. . . [steel using industries] lost more jobs than exist in the steel industry.”

- A group of supply chain and operations management experts from Georgia State University, Colorado State University, Arizona State University, and Kuwait University found that the U.S. tariffs enacted in 2018 had a ripple effect of unintended consequences that negatively affected global supply chains. The group concluded that these tariffs had “an overall negative impact” on firm value that led to a decrease in the value of domestic producers within the protected industries.

- The 2018 U.S. tariffs increased costs by $51 billion/year—a burden shouldered principally by U.S. companies and consumers. (NB: Per the Federal Reserve, while 1,000 jobs were added to the steel industry, 75,000 jobs were lost among industries using steel.)

- Tariffs of the permanent (rather than tactical/semi-strategic) type tend to run afoul of the “Law of Unintended Consequences.”

Trade Wars and Tariffs

Supply managers have been warned for years that it is difficult to manage supply chain risk when buying products from (1) manufacturers a long distance away and (2) potential adversaries, says Timothy R. Fiore, CPSM, C.P.M., chair of the Institute for Supply Management® (ISM®) Manufacturing Business Survey Committee. “Supply managers should be prepared for this,” he says. “In actuality, we likely are not.”

According to The Economist, China claims its exports to America rose by $30 billion between 2020 and 2023, whereas the U.S. claims Chinese imports fell by $100 billion.[6] Sometimes, words simply fail. . . .

According to the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office, President Trump’s campaign pledges would add an estimated $7.75 trillion to the projected debt through FY 2035, part of which is expected to be offset by revenue estimated at $2.7 trillion to $4.5 trillion generated by increased custom duties. Per the National Retail Federation, currently proposed tariffs could cost U.S. consumers as much as $78 billion a year in annual spending power.

No matter which side of the political aisle one feels most comfortable occupying, tariffs always hurt the country imposing them. See Table 3.[7]

*These figures quantify the impact of tariffs on various prices and sectors. They isolate the impact of tariffs from other macroeconomic and industry trends. The figures are based on econometric modeling by the Hartford’s Global Insight Center and findings from other researchers.

The Role of Politics, Both Domestic and Global, on Global Trade and Supply Chains

Politics – Domestic

To take only a single aspect of the current “deportation of illegal aliens” dialogue as an example, deporting children of illegal immigrants born on U.S. soil (“Dreamers”) would deplete the U.S. workforce of ~300,000 future U.S. workers at a time when the U.S. is at full employment (i.e., at 4.2% as of the end of May). Losing this many workers would create a future disaster. Where, exactly, will the workers come from to fill the void? The U.S. birth rate is below replacement rate, so future workers essential to maintain GDP will not come from within the borders of the United States. Period.

Deporting 7MM? 9MM? 11MM? (pick a number) of illegal immigrants will affect the following areas in what ways and to what degree?

- Seasonal harvesting—the U.S. is currently experiencing a significant shortage of career and seasonal farm workers

- Seasonal farmworkers aging out—resulting in higher prices to consumers and putting some farms out of business

- Migrant workers are not illegal immigrants and nor are they deadbeats—they are mandatory for maintaining a healthy economy, both now and into the future.

- Illegal immigrants are not automatically criminals, other than for committing the crime of crossing the border without permission—the clear majority of “illegal immigrants” have no criminal records.

- In fact, according to U.S. Customs and Border Security, of the 11 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S., only 3% are convicted felons, and an additional 4% have non-felony convictions.[8]

- Per the University of Georgia, however, of the 341 million U.S. citizens, 8% are convicted felons and 20% have non-felony convictions.[9]

- We are coming precipitously close to doing what the Germans call “Das Kind mit dem Bade ausschütten”—“throwing the baby out with the bathwater”

Tariffs only enrich the U.S. Federal Government’s General Fund—U.S. consumers are not given a portion of the tariff to help offset higher prices. . . .And prices will be higher. If the U.S. hits China with a 10% tariff on Tupperware®, the U.S. Government will collect 10% on all Chinese Tupperware® sold to U.S. consumers. But, before you can say “consumer savings,” the retailers will raise the price of Tupperware® by 10%, so it is the consumer who actually pays the cost of the tariff, not the Chinese manufacturers, AND increasing consumer prices automatically causes inflation that cannot easily be checked by FED fund controls.

Politics – Selected Geopolitical Concerns

- Changes in supply

- China used to produce copper phthalocyanine pigments for finishing in India

- China is now able to manage the entire Cu/phthalo supply chain internally, from basic reactions, to drying and finishing

- This is affecting one chemical after another

- Concerns about trade route security/stability

- Houthis in the Red Sea

- Potential blockading of the Strait of Hormuz by Iran

- Possible American interference in Panama

- Importance of GIUK (Greenland, Iceland, United Kingdom) Gap? Real? Perceived? Military only? Maritime only? Both military and maritime?

- Implications of Russia/Ukraine War

- Negotiated settlement

- Enforced settlement

- Continued warfare—including the role of North Korean miliary personnel and Chinese munitions?

- Increasing dissatisfaction with China by both the U.S. and EU

- Tariff issues

- Concerns over Taiwan

- Support, albeit minimal, for the Russians in the War Against Ukraine

- Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)

- Silk Road Economic Belt

- 21st Century Maritime Silk Road

- Polar Silk Road

- Other components of BRI

- Degenerating diplomatic relationships—we are in a “Geopolitical Recession,” which is characterized by Borge Brende, president of The World Economic Forum, by global fragmentation and polarization, leading to less cooperation and more competition than in the past

- Supply concerns—China produces:

- 42% of all epoxy resin

- 44% of all chemicals

- 50% of the world’s steel

- 70% of all rare earth ore

- 90% of all refined rare earth metals

The Great Supply Chain Crisis of 2021-2023

The major disruption in global supply chains initiated by the COVID-19 pandemic, and intensified by the “Big Freeze” in the Permian Basis (principally Texas) in February 2021, was characterized by:

- Major bottlenecks at ports

- Labor shortages

- Increased demand for certain goods, leading to:

- Delays in deliveries

- Product shortages

- Price increases for consumers across various industries

- Panic ordering by both desperate producers and customers

The pandemic triggered lockdowns, which caused sudden changes in consumer demand, factory closures, labor shortages at ports and production facilities, and major disruptions in the flow of goods. As a result, consumers experienced longer delivery times, empty shelves, and higher prices. In addition, the availability of common household necessities (e.g., paper goods, disinfectants, and many food items) was critically curtailed, and there was significant R/M reduction/destocking following the end of the crisis. A basket of coatings R/Ms, indexed to 2019 vs. selected coatings R/M component prices, increased 40-50% from the first quarter of 2020 to the fourth quarter of 2022. Industries such as electronics, automotive, and consumer goods were particularly impacted, and recent events like the Russia-Ukraine conflict further exacerbated supply chain issues, particularly in energy and commodity markets.

Timeless Lessons Learned from The Great Supply Chain Crisis

The lessons the world learned following The Great Supply Chain Crisis will continue to be of use as geopolitical, economic, and other challenges impact the supply chain. Specialty chemicals companies should particularly remain cognizant of issues related to raw material supply, logistics, customers, and research and development.

Raw Material Supply

Every raw material used to make paint and coatings in the U.S. should have at least one reliable vendor in the U.S. that either makes the material in the U.S. or has significant stocking capability in the U.S. to keep the regional supply chain filled with material the next time the global supply chain is thrown off kilter. Having a single source of any raw material is a bad idea. Instead, whenever possible, have alternate raw materials (and alternate suppliers) approved for every raw material that is used in routine production. Every producer should have multiple suppliers whenever possible (at least 2-3), so that it has a purchasing record with companies other than its primary supplier. Violation of this rule should be tolerated only due to the absence of a second source. In addition, certain high-profile manufacturing operations should be repatriated to the U.S., as should the ancillary suppliers to those industries.

Logistics

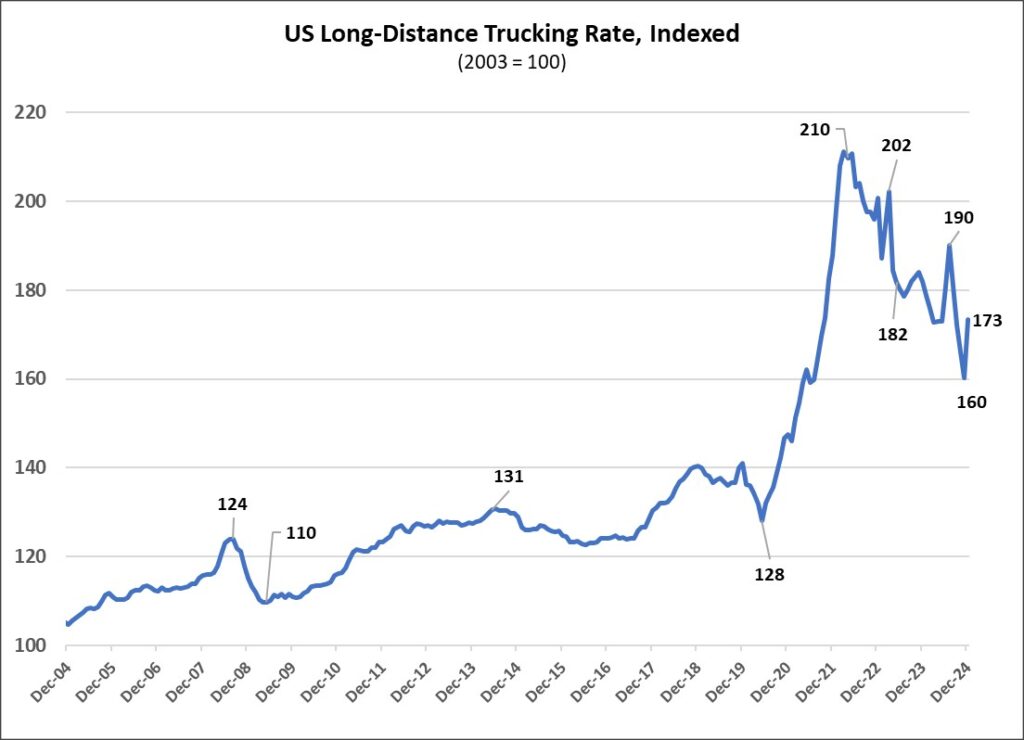

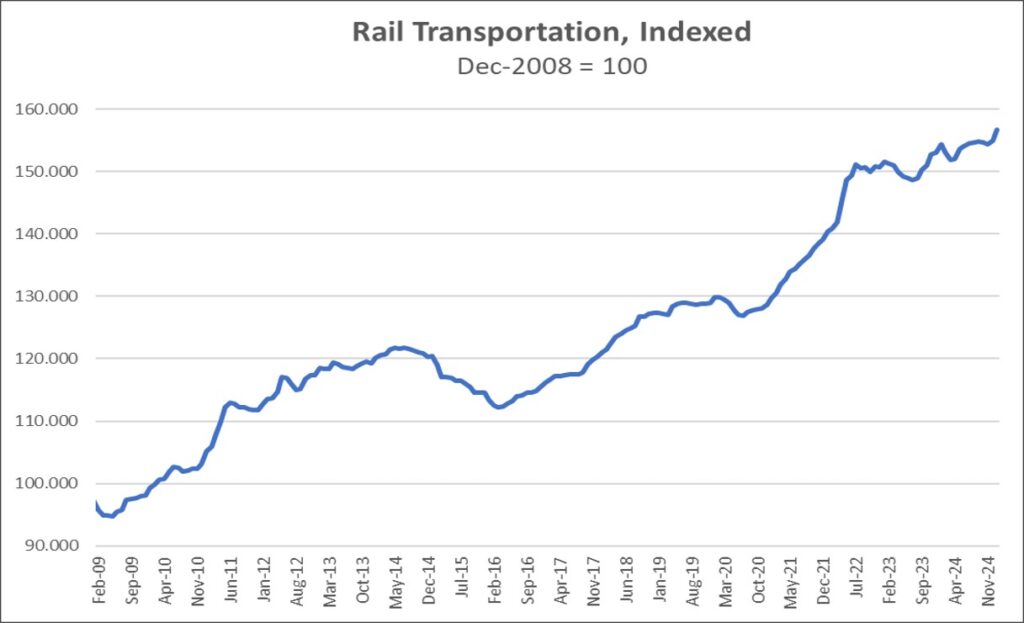

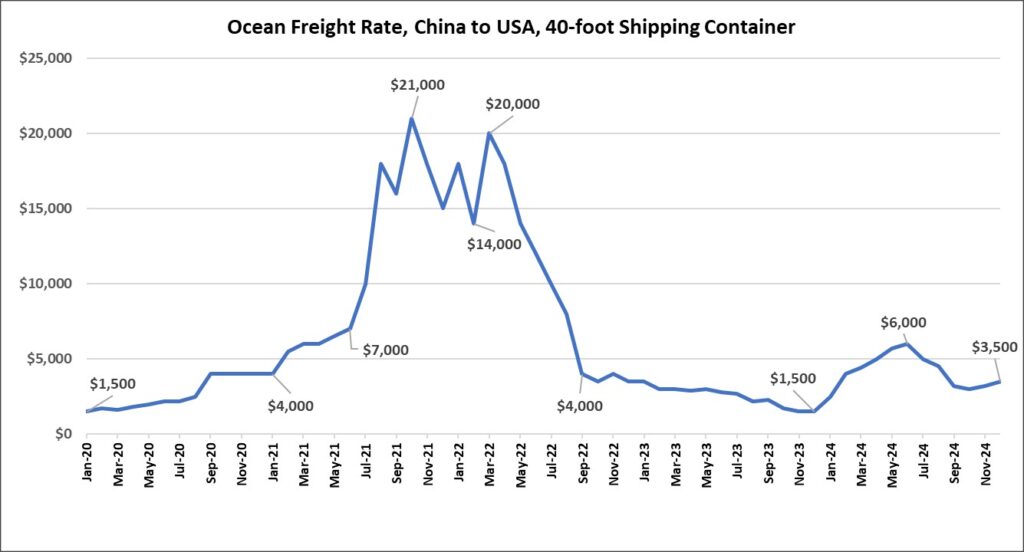

One of the most devastating aspects of The Great Supply Crisis was the inability to ship and receive goods, even when there was supply and orders could be filled. Containers were often in ports where they could not be easily retrieved, and panic orders were so high that there would have been insufficient containers to carry the goods, even if they had been in more convenient locations. Ships were stacked up at ports where there was insufficient manpower to unload them and too few trucks to provide intermodal transportation from the docks to the final destination. Cost-to-ship rose dramatically, and the entire global trading community had to sit helplessly by because so little could be done to rectify the situation in anything approaching real time. See Figures 4, 5, and 6.

The message here is both easy to visualize and difficult to achieve: Availability of raw materials is of little value if they cannot be transported to the facility that will turn them into saleable products. Manufacturers absolutely must be building reliable logistics capability now, and pressure testing their processes and procedures in real time to make sure that when the next supply chain crisis hits, they will have the maximum ability to transport materials from the source to their production facilities.

Customers

Both raw material suppliers and their customers, whether they are producing paints and coatings, adhesives, lubricants, household cleaners, or anything else in the specialty chemicals value chain, rate their customers and suppliers (officially or unofficially) on an “A,” “B,” “C” scale:

- “A” suppliers/customers—Partnerships; purchases made on overall value, not lowest price; loyalty; fair payment terms; on-time delivery; overall quality; quality of technical service; quality of sales service—are they merging these days?; significant history of working together, and clear establishment of trust; etc.

- “B” suppliers/customers—Mixtures of “A” and “C” characteristics. . . What does it take to turn a B customer into an A customer? How about turning a B customer into a C customer? When are these changes most likely to happen?

- “C” suppliers/customers—Chase every penny down the rabbit hole; consolidate purchases with minimum number of products to obtain pricing; indulge in hoarding behavior; treat R/M suppliers as if they were bankers; are guilty of poor forecasting; have excessive “RUSH” orders; refuse to pay small-batch upcharges; etc.

During good times, it is possible to have an “A-B-C” classification without the need to take specific action on it. Business is good, orders are heavy, time is limited—so little thought is given to the overall effect that different raw material suppliers and customers are having on your bottom line, much less on your supply chain. During hard times, however, it is important to make sure that those suppliers and customers that enable you to realize the highest value for your business absolutely must be the focus of your attention. If you are a resin producer with only a single tank wagon of a resin that six of your customers are begging for, and one of them is a small but growing “A” customer and another is a very large but excessively demanding “C” customer, give some serious thought to rewarding the small “A” customer. You are likely to find that your action is rewarded many times over.

Research & Development

The development of new and significantly improved products are the lifeblood of any producer’s efforts to enhance its market share in the specialty chemical industries, such as paints and coatings; sealants and adhesives; HI&I; lubricants; personal care; and many others. Absolutely nothing should prevent at least a minimum amount of true R&D from taking place, even during the darkest hours when all hands are on deck trying to put out fires. Coatings is a technology-based, global industry—those with a strategy focused on the continual development of new and improved products will be the winners.

Closing Thoughts

More than anything else, we need to learn from the past, including from the recent, post-COVID past. Developing resilient and transparent supply chains is at the top of the list, when it comes to being prepared for geopolitical shifts that might affect global supply chains. This is closely followed by building a geopolitical view from the perspective of your own company. It doesn’t require additional computation power or fancy systems, but it does require that everyone within the specialty chemical value chain, whether producers of raw materials or final products, such as coatings and adhesives, become more familiar with what’s going on in the world and how it might affect them. This is the only way to be prepared for eventualities that may or may not occur, but being prepared is the only way in which anyone can be protected from those that DO occur. Become informed about your supply chain—those who purchase a mixed metal oxide pigment containing cobalt should at the very least know what is happening in the cobalt mines in The Democratic Republic of Congo. This is not an unreasonable step to take—if you need a cobalt-based colored inorganic calcined pigment (CICP) in your paint products, you will need this knowledge to protect your supply. Enhance your organization’s ability to sense and respond to changing geopolitical landscapes—encourage the appropriate parties in your organizations to read The Economist; Financial Times; and The Wall Street Journal. Never view the time spent studying these publications as “wasted” or “down” time—we live in a new age, and it requires that we be knowledgeable about different issues that may have been of significantly less importance in the past.

Along with these actions, provide whatever in-house or outside training is necessary to strengthen decision-making processes to remain agile and to enable your company to embed geopolitical scenarios and analysis into capital allocation and strategic planning. Make a concerted effort to expand your presence in growth markets—what was once a “hope for the future” should now be considered to be “what is need right now.” Above all, embrace smart nearshoring, friendshoring, and reshoring. These are not merely slogans designed to get industry participants excited about changing the future—they are the means by which industry participants will be able to change the future.

Finally, it is understandable that not every company can invest in regional differentiation, but there are many raw material and finished product producers who could, if they tried. In our current geopolitical climate, it is better to try and fail, than not to try at all. Most companies are capable of doing far more than they give themselves credit for, so challenge those items that the organization is sure that it cannot do—and, when in doubt, give the author a call at The ChemQuest Group. We’ve spent the past 49 years helping members in the specialty chemical chain do things that they never dreamed were possible.

Bottom Line

As global trade fragments and regionalization accelerates, organizations will need to adopt differentiated structures and technology stacks—a one-size-fits-all approach will no longer suffice. Neither does it make sense to do everything on your own, when help is available. Try not to think in terms of “inside help” and “outside help.” This is a misleading differentiation that has prevented many, many organizations within the specialty chemicals value chain from realizing their full potential. Now is not the time to “do it all on your own.”

To learn more, reach out to the author at gpilcher@chemquest.com.

References

1. “Smarter growth, lower risk: Rethinking how new factories are built,” McKinsey & Co., February 24, 2025, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/operations/our-insights/smarter-growth-lower-risk-rethinking-how-new-factories-are-built.

2. “Great Powers, Geopolitics, and the Future of Trade,” BCG, January 13, 2025, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2025/great-powers-geopolitics-global-trade.

3. “How business leaders can proactively navigate geopolitics,” McKinsey & Co., https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey-live/webinars/how-business-leaders-can-proactively-navigate-geopolitics

4. Ibid.

5. “Great Powers, Geopolitics, and the Future of Trade,” BCG, January 13, 2025, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2025/great-powers-geopolitics-global-trade.

6. “Trump and Biden have Failed to Cut Ties with China,” The Economist, February 27, 2024, https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2024/02/27/how-trump-and-biden-have-failed-to-cut-ties-with-china.

7. “Tariffs: The Crossroads of Geopolitics and Economics,” The Hartford, May 19, 2025,https://www.thehartford.com/insights/economic-trends/tariffs-geopolitical-economic-consequences

8. Criminal Alien Statistics, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/cbp-enforcement-statistics/criminal-noncitizen-statistics

9. “Criminal Repercussions,” University of Georgia, https://research.uga.edu/news/study-estimates-total-u-s-population-with-felony-convictions/#:~:text=People%20with%20felony%20convictions%E2%80%94including,the%20African%2DAmerican%20male%20population.

Read in ipcm.